RL Grokking Recipe: How Can We Enable LLMs to Solve Previously Unsolvable Tasks with RL?

TL;DR

-

We introduce DELTA: a controlled suite of synthetic programming families with fully OOD splits and verifiable rewards. DELTA lets us ask two crisp questions: Learnability (can RL solve families where the base model has pass@K=0?) and Transferability (do the learned procedures generalize?)

-

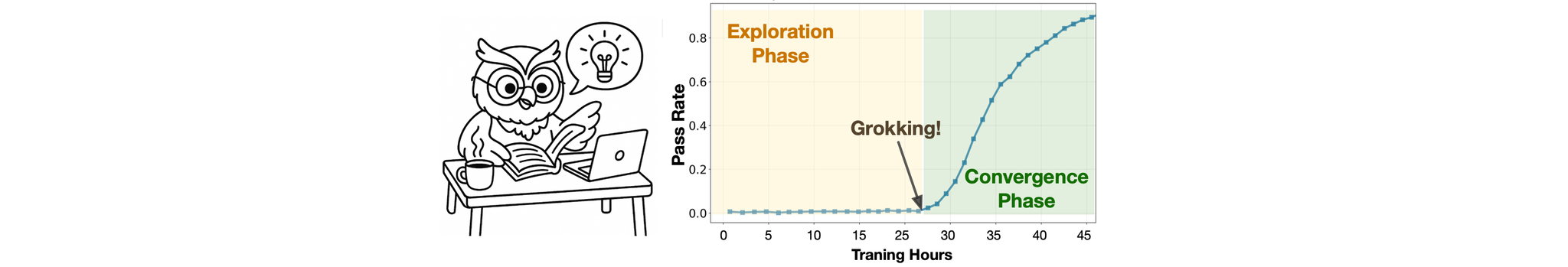

On several pass@128=0 families, RL exhibits a grokking-like phase transition: after a long near-zero-reward plateau, accuracy snaps to ~100%. That is discovery, not mere sharpening.

-

A two-phase reward schedule is key: dense per-test rewards to escape the “all-zero” region, then binary full-pass to consolidate exact solutions. Binary-only gets stuck; dense-only hovers at “almost right.” The schedule yields the grokking jump.

-

Transfer is selective: RL-trained policies recompose programming sub-skills and extrapolate to harder parametric regimes, but struggle on transformative shifts that require new invariants.

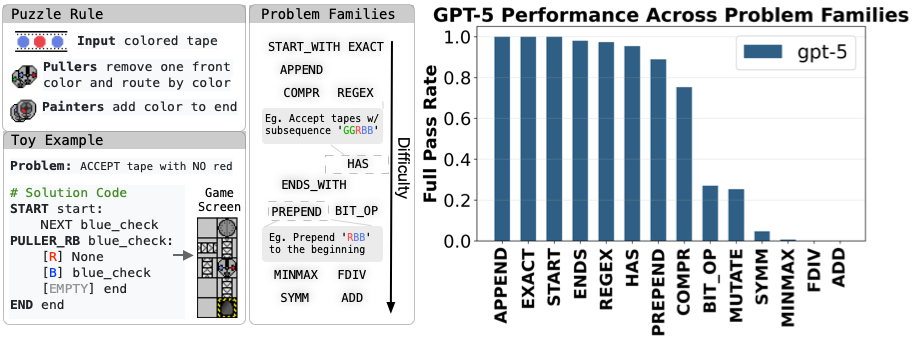

Manufactoria: a pure OOD learnability testbed

Manufactoria is an old Flash game from 2010 where you test robots by reading colored tapes. We took that core idea and turned it into a clean, programmable playground for studying learnability. Some problems are so challenging that even advanced LLMs like GPT-5 would have a 0% success rate!

Instead of a 2D puzzle grid, we expose a minimal program syntax with just two primitive “machines”: a puller (reads/moves) and a painter (writes/marks). Think of it as a tweaked Turing machine where the reader is only allowed to operate on the left side of the tape and the writer is only allowed to operate on the right.

Why this is truly out-of-distribution (OOD)

New language, not on the internet. The original game’s solutions lived as screenshots on old forums. Our textual program format is brand-new, so pretrained LLMs haven’t seen it.

Fresh puzzles, not recycled levels. We synthesized new problem families inspired by the mechanics, not copies of any published challenges.

Different reasoning than code-as-usual. With only puller and painter, you don’t get normal control flow or rich data structures. You get finite-state, tape-shuffling tricks: routing, buffering, parity checks, pattern filters—strategies you won’t pick up from standard programming corpora.

Why we care

This quirky problem setup forces models (and humans!) to invent distinctive reasoning patterns: encode a color, ferry it across, compare it later, branch with almost no existing syntax sugar. If an RL-trained model improves here, it’s unlikely riding on memorized code idioms—and more likely learning real strategy in a space where “read” and “write” operate on opposite ends of the world.

Why do people think RL can’t escape the base model’s “invisible leash”?

The intuition behind the skepticism.

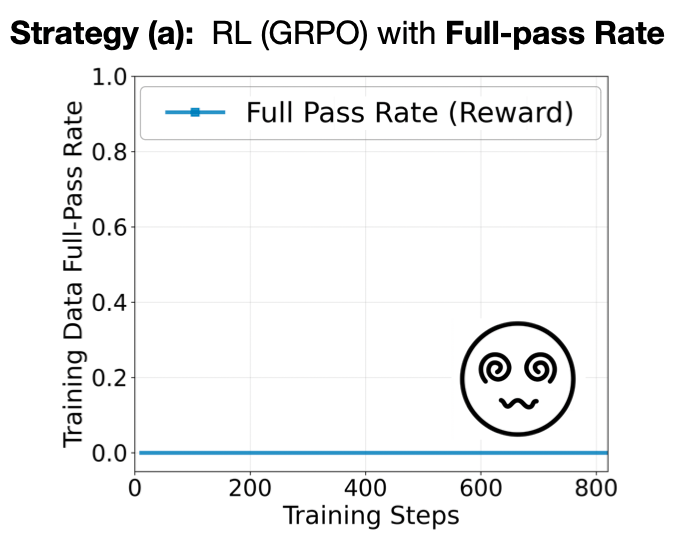

Most RL-for-reasoning pipelines (GRPO/PPO variants) update the model by comparing rewards across multiple rollouts of the same prompt. If none of the rollouts solve the task (pass@K=0), the reward landscape looks flat (see figure below): every sample is equally bad, so the gradients vanish.

Empirical patterns that reinforce the belief.

Binary-only training stalls. With strict full-pass rewards, early training steps are stuck in an all-zero regime—no success, no learning signal.

Coverage/perplexity arguments. If the base model’s support doesn’t contain the right programs, how could RL “conjure” them? Skeptics conclude RL can only reweight what’s already there, not invent new strategies.

A Side note regarding the reward type:

Full-pass rate (binary reward).

What it is: Success only if all tests pass. Reward = 1 if passes every test, else 0.

Per-test pass rate (dense reward).

What it is: The fraction of unit tests a program passes. If there are N tests and a rollout passes m, reward = m/N.

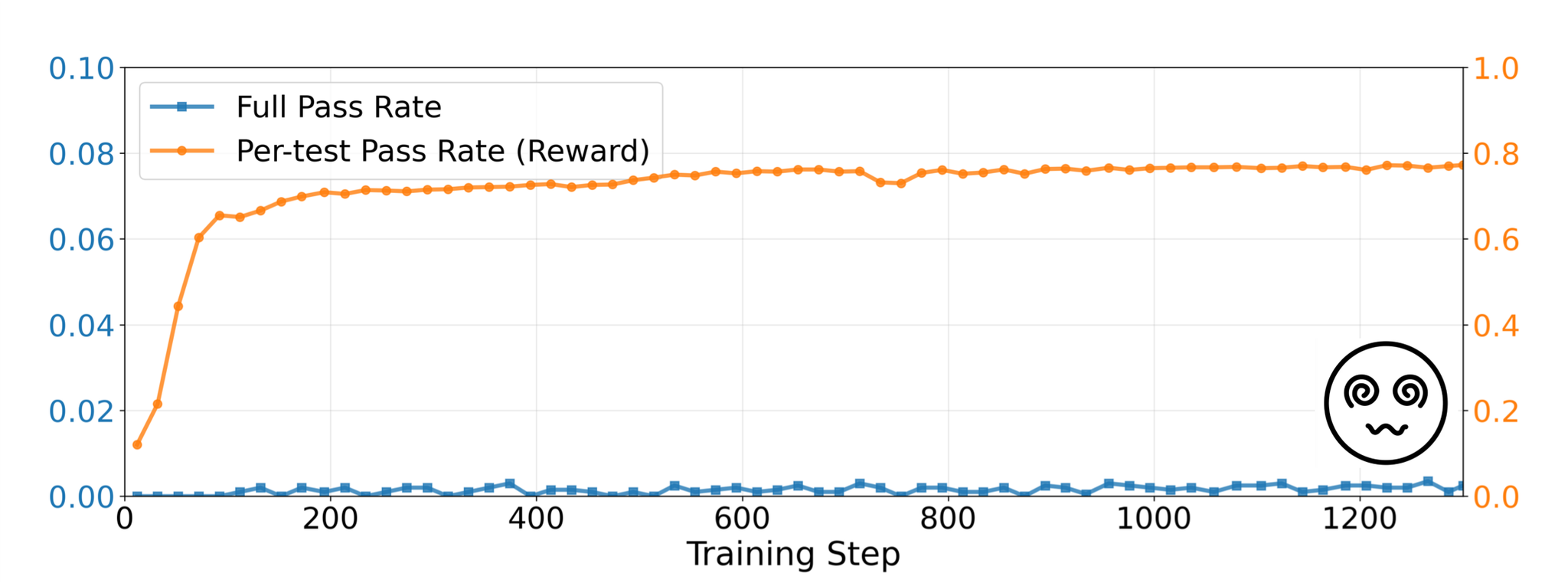

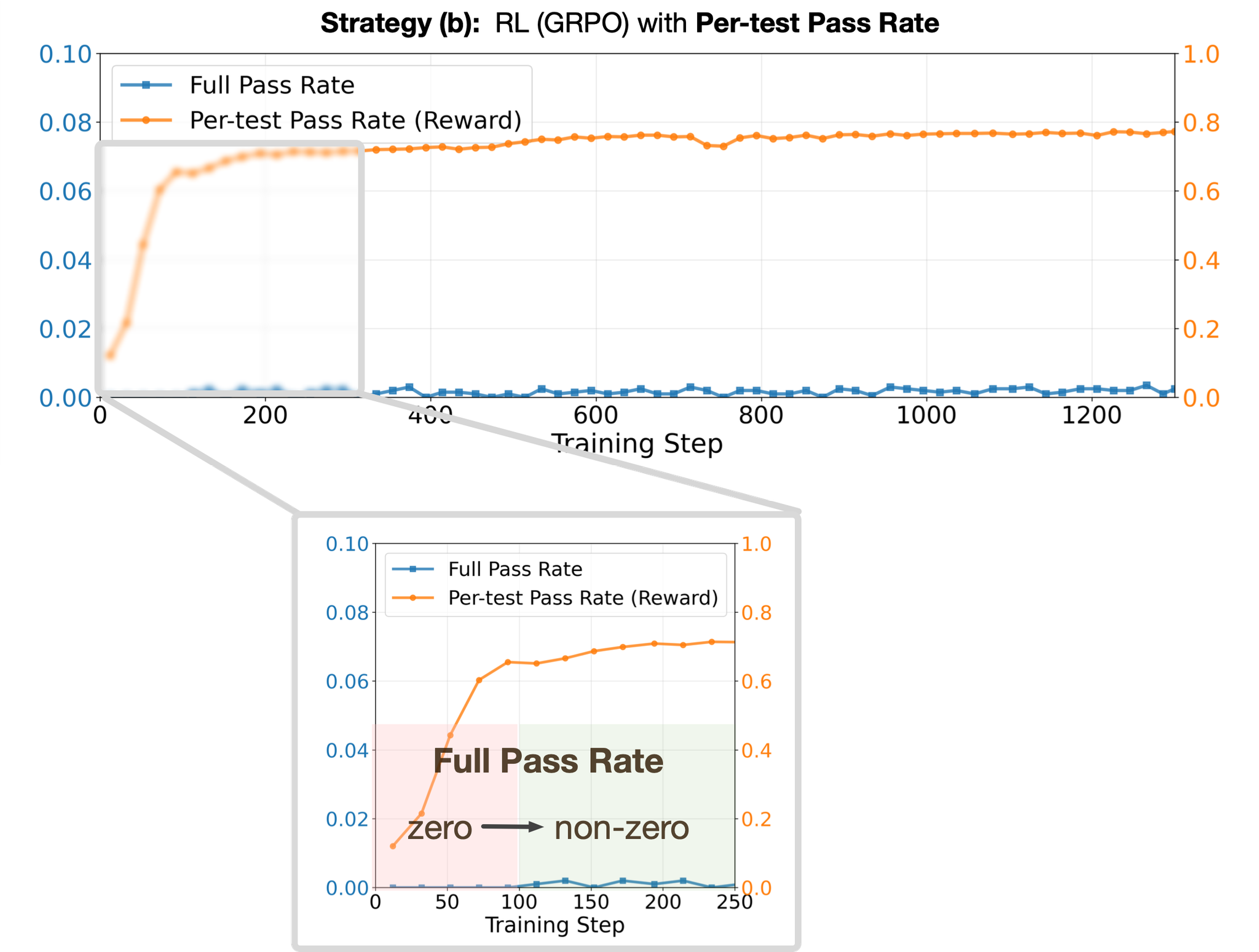

If full-pass creates the problem, should we just use per-test rewards?

Why per-test helps (and why it plateaus).

What it fixes: Per-test pass rate turns “all-or-nothing” into “how many tests did you pass?”, creating dense reward in [0,1]. Even half-working code earns partial credit, so gradients stop being zero.

What it doesn’t fix: Dense rewards do not enforce exactness. As shown in the figure below, they can saturate when the model learns to pass “the easy tests” or exploits correlations that bump the average—leaving the full-pass rate near zero. You get almost right forever.

Wait! The full pass rate is no longer exactly zero. It’s tiny, less than 0.2%, yes. But critically, we’ve pulled the model out of the absolute zero region.

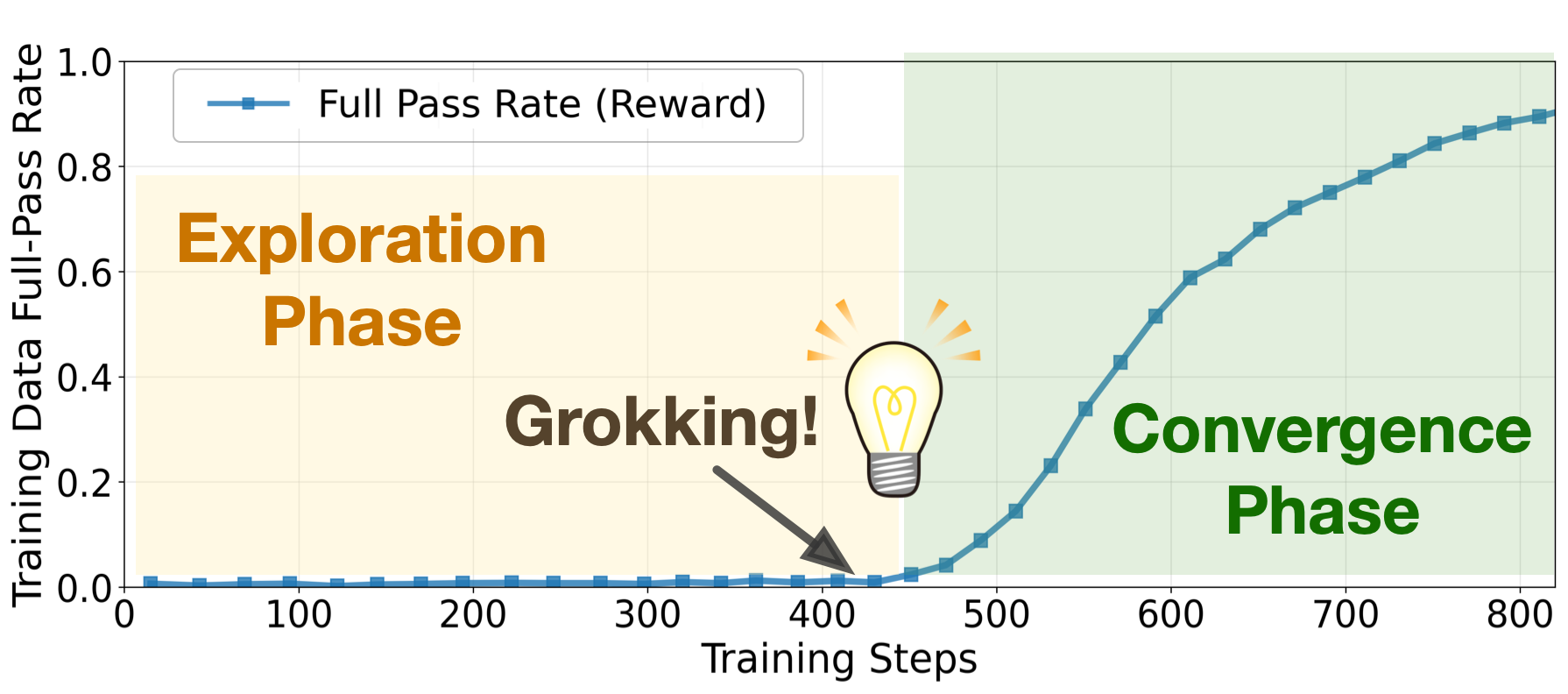

Okay—now flip back to full-pass (and watch what happens)

You’ve used per-test to break out of the all-zero regime. Great. Now take the training wheels off.

Phase B: switch to binary full-pass.

From this warm-up checkpoint, we switch to RL with the binary full-pass reward. The figure above illustrates the dynamics: For ~450 steps, the model remains in an exploration phase, with full-pass rate still <1%. After a sudden grokking moment, the model discovers the key strategy to solve the family. Training then enters a convergence phase, where RL sharpens and consistently reinforces the successful reasoning path. At convergence, the RL-trained model achieves nearly a 100% absolute improvement in pass@k compared to the reference model.

In our paper, we demonstrate this grokking phenomenon across multiple problem families and models.

Beyond learnability: can the learned skill transfers?

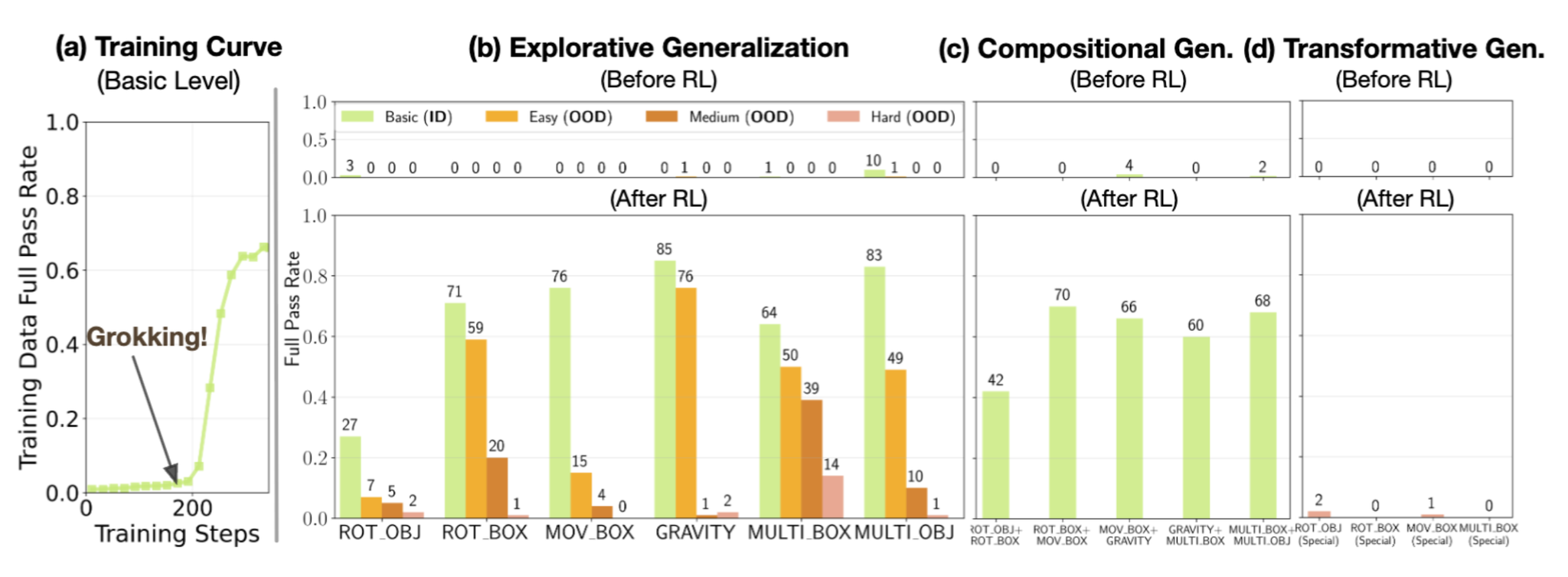

You’ve probably seen “bouncing balls in shapes” tests for LLM coding, judged visually on X.com. We turn that into BouncingSim: each instance specifies a 2D scene (rotating/moving boxes, gravity, multi-ball), and the model must output the exact trajectories, graded by deterministic unit tests.

We use it to probe three axes of generalization:

Exploratory 🧭: harder scenes (more vertices, higher bounciness). Does the learned collision logic extrapolate?

Compositional 🧩: recombine primitives (multi-ball + moving boxes). Can the policy stitch sub-skills without collapsing?

Transformative 🔄: train on common variants; test on qualitatively different dynamics, such as special initial conditions that produce perfectly periodic bounce trajectories

What we see: 📈 RL shows the classic grokking fingerprint: a long flatline followed by a phase transition around step 200, rising to about high full-pass after grokking. This signals the emergence of a stable elastic-collision simulator.

Beyond train, transfer is selective: strong when the shift allows the model to recompose structure (composition), weak when it requires discovering new invariants (transformative).

Discussion and Implications for Future Study

Two RL regimes: sharpening vs. discovery

From these controlled studies, we see two valid modes:

Sharpening. RL compresses variance and stabilizes known strategies: pass@1↑ without expanding the support at large K.

Discovery. RL crosses a learnability gap: pass@K=0 → sustained solves after training, with a distinct phase transition in the learning curve. Which regime you get depends on reward topology, exploration duration, data mixture, and task hardness.

Measure what matters: the hard frontier (pass@K=0)

Averages over heterogeneous pools mask the frontier where novelty shows up. On the pass@K=0 subset, RL often exhibits a grokking-like jump after hundreds of steps; in mixed pools, that signal gets diluted. We argue evaluations should track this subset explicitly.

Why coding first—and what’s next for math & science

Coding is the perfect RL beachhead: unit tests give cheap, precise, fine-grained rewards, and reusable subroutines enable natural skill recomposition. The same lesson can port to math & science wherever we can engineer fine-grained evaluators: rubric scoring, step checkers, lemma reuse, theorem-prover or simulator feedback, etc. Treat the evaluator as first-class infrastructure, and RL can bridge from “no successes” to genuine discovery.

Takeaways

- Controlled families + verifiable, staged rewards transform “all-zero” regimes into learnable ones.

- Grokking is a reliable signature that the model has found an algorithmic procedure, not just sharpened sampling.

- To push RL into the discovery mode, optimize the reward topology and curriculum, not just the model size.

If you find this blog useful, we would appreciate it if you could cite our work:

@misc{sun2025rlgrok,

title = {RL Grokking Recipe: How Does RL Unlock and Transfer New Algorithms in LLMs?},

author = {Yiyou Sun and Yuhan Cao and Pohao Huang and Haoyue Bai and Hannaneh Hajishirzi and Nouha Dziri and Dawn Song},

year = {2025},

month = {sep},

eprint = {2509.21016},

archivePrefix = {arXiv},

primaryClass = {cs.LG},

doi = {10.48550/arXiv.2509.21016},

url = {https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.21016}

}